WuBlockchain Published with Authorization

With the evolution of financial technology and shifts in global geopolitics, governments around the world are gradually recognizing the immense potential of stablecoins. Countries and regions such as the European Union, the United States, Singapore, and Hong Kong have initiated consultations and legislative activities to secure a competitive edge in the future. On August 15th, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) announced the final version of its regulatory framework for stablecoins, becoming one of the first jurisdictions globally to incorporate stablecoins into its local regulatory system. In the near future, both Hong Kong and the United States will introduce regulations for stablecoin oversight, making Singapore’s recent regulatory framework release of significant value. To some extent, it will serve as a template for regulatory authorities worldwide. In this regard, this article will provide an in-depth analysis of Singapore’s stablecoin regulatory framework, shedding light on the future trends in global stablecoin regulation.

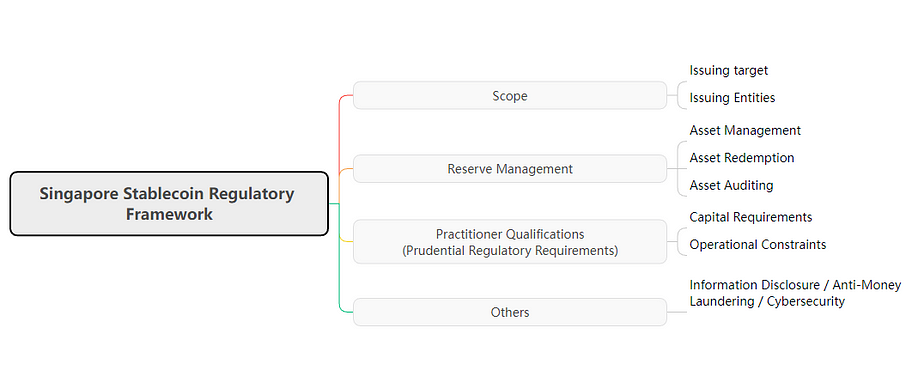

Key Points of Singapore’s Stablecoin Regulatory Framework

The earliest regulatory attempts by MAS regarding stablecoins can be traced back to the Payment Services Act (PS Act) introduced in December 2019. Subsequently, in December 2022, MAS issued consultation papers to seek public opinions on the proposed stablecoin regulatory framework. On August 15th of this year, MAS finalized the stablecoin regulatory framework. Therefore, Singapore’s comprehensive regulatory framework for stablecoins encompasses the content of these three regulatory documents, rather than just one. Based on my analysis, Singapore’s stablecoin regulatory framework mainly consists of the following aspects:

1. Scope of Application

A notable aspect of Singapore’s newly introduced stablecoin regulatory framework is the openness of stablecoin issuance targets. MAS allows the issuance of single-currency stablecoins (SCS) pegged to a single currency anchor. The currency anchor is the Singapore Dollar (SGD) plus G10 currencies. Generally, a nation’s currency symbolizes its sovereignty, and other countries do not have the authority to manage it. However, MAS permits stablecoins pegged to the currencies of other countries, signifying a significant breakthrough. This shows MAS’s openness and innovation, taking into account the national situations of G10 countries and engaging in communication with various nations.

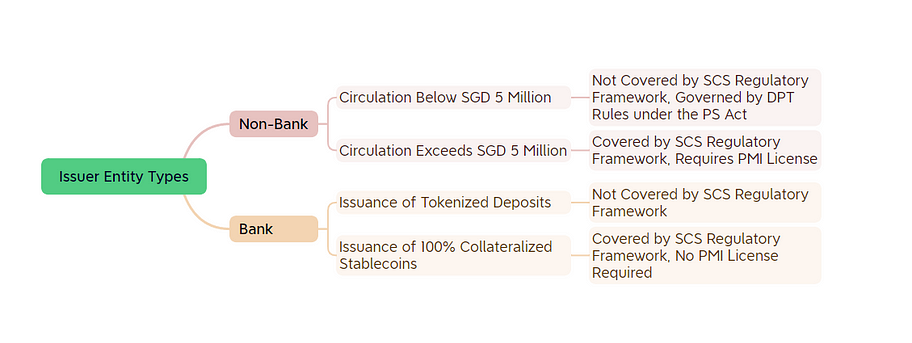

Furthermore, in terms of the issuer, MAS has made significant adjustments. MAS classifies stablecoin issuers into two categories: banks and non-banks. For non-bank issuers, MAS requires stablecoins with a circulation size of over SGD 5 million to be included in the stablecoin regulatory framework, and these issuers need to apply for the Major Payment Institution (MPI) license under the PS Act. Otherwise, they fall outside the scope of stablecoin regulation and only need to comply with the Digital Payment Token (DPT) provisions of the PS Act. For banks, MAS initially planned to include tokenized deposits under the stablecoin category, but due to significant differences in the nature of assets (deposits are products of the reserve system of banks, not 100% collateralized, and are considered bank liabilities), they were excluded. Thus, banks are required to issue stablecoins with 100% asset collateralization. It’s worth noting that banks do not need to apply for an MPI license. MAS explained that the Banking Act already mandates that banks meet relevant standards.

2. Reserve Management

In terms of reserve management, MAS has established detailed regulations, mainly focusing on the following areas:

Firstly, regarding the composition of assets, MAS requires that reserves are only allowed to be invested in cash, cash equivalents, bonds with a remaining maturity of no more than three months. MAS has also provided specific qualifications for the issuing entity of these assets: they must either be currency cash issued by governments/central banks or bonds rated AA- and above by international agencies. It’s noteworthy that MAS has provided a restrictive interpretation of cash equivalents: it primarily refers to bank institution deposits, checks, and drafts that can be rapidly paid and liquidated, excluding money market funds. Therefore, stablecoins similar to USDC, which invest 90% of their assets in money market funds, or even stablecoins like USDT that invest in commercial papers, do not comply with MAS regulatory requirements.

Secondly, concerning fund custody, MAS mandates that the issuer establishes a trust and opens a segregated account to separate its own assets from reserves. Qualifications for fund custodians are also clearly specified: they must be financial institutions holding custody service licenses in Singapore, or overseas institutions with branches in Singapore and credit ratings not lower than A-. As a result, stablecoin issuers seeking inclusion in MAS’s regulatory framework must collaborate with a local financial institution in Singapore or a financial institution with branches in Singapore.

Lastly, in terms of day-to-day management, MAS requires that the daily market value of reserves be higher than 100% of the circulation size of SCS. During redemption, reserves must be redeemed at face value, and the redemption period should not exceed 5 days. Monthly audit reports must also be published on the official website.

3. Qualifications for Practitioners

An eye-catching aspect of this regulatory framework is MAS’s detailed provisions regarding the qualifications of stablecoin issuers, which is a part of its prudent regulation. MAS has laid out qualifications for stablecoin issuers in three main areas:

Firstly, there is the Base Capital Requirement, which is somewhat analogous to the Basel Accords’ requirement for banks’ own capital. MAS stipulates that the capital of stablecoin issuers must not be less than SGD 1 million or 50% of the annual operating expenses (OPEX).

Secondly, there are Solvency Requirements. These necessitate that liquid assets exceed 50% of the annual operating expenses or meet the scale required for normal asset withdrawals, with this scale needing to be independently verified. It’s important to note that MAS has explicitly specified the categories of liquid assets, primarily encompassing cash, cash equivalents, government bonds, large certificates of deposit, and money market funds.

Lastly, there are Business Restriction Requirements. These demand that stablecoin issuers refrain from engaging in activities such as lending, staking, trading, and asset management, and they are not permitted to hold shares in any other entity. However, MAS has also made it clear that stablecoin issuers can engage in stablecoin custody and the transfer of stablecoins to purchasers. This effectively limits stablecoin issuers from conducting diversified operations. Furthermore, MAS explicitly states that stablecoin issuers are prohibited from paying interest to users through activities like lending, staking, and asset management. Other companies, though, can offer similar services for stablecoins, including sister companies that stablecoin issuers do not hold shares in.

4. Other Regulatory Requirements

MAS has also established regulations for information disclosure, qualifications and restrictions for stablecoin intermediaries, cybersecurity, and anti-money laundering, among other areas. However, these provisions do not warrant specific attention, so this article refrains from delving into further analysis. Readers interested in these aspects can refer to the relevant documents for more information.

Assessing the Gains and Losses of Singapore’s Stablecoin Regulatory Framework

The establishment of Singapore’s stablecoin regulatory framework holds significant implications for the compliant development of the global stablecoin industry, as well as providing a model for other countries. This article will focus on several areas where the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) could continue refining its framework.

MAS’s stablecoin regulatory framework, though comprehensive, has left certain crucial aspects unresolved or ambiguous, potentially posing challenges in the near future.

1. Reserve Asset Composition: Initially, MAS intended that reserve assets must be denominated in the same currency as the anchored currency. However, this poses a critical issue — users are concerned about the ability to deposit and withdraw stablecoins in currencies such as the US Dollar. If the stablecoin can only be exchanged for Singapore Dollars, it may lack a competitive edge and lead to a small issuance volume. Additionally, the range of investable assets for certain anchored currencies is limited, presenting a significant challenge for reserve asset management. MAS acknowledges these concerns but refrains from explicitly permitting the use of different currency assets for reserves, merely reiterating the need to manage risks and maintain a 100% reserve.

2. Cross-Jurisdictional Issuance: To address cross-jurisdictional issuance, MAS proposed two solutions — submitting annual documentation to prove alignment with other jurisdictions or establishing collaborations. However, due to practical constraints, these approaches have proven unfeasible. Consequently, MAS restricts stablecoin issuers from conducting cross-jurisdictional issuance during the initial stages. Yet, numerous stablecoins have become global, issued across different regions and blockchain networks. Complying with MAS’s requirement could lead to diminished market competitiveness for these issuers.

3. Regulation of Systemically Important Stablecoins: While MAS’s consultation paper in the past year defined systemically important stablecoins and aimed to regulate them according to financial market infrastructure standards, the current framework has opted to postpone addressing this controversy and observe future developments.

Apart from the regulatory content itself, another vital question concerns the benefits and drawbacks of launching compliant stablecoins in Singapore.

On one hand, the advantages of compliant stablecoins lie in their regulatory compliance. The confidence instilled by their regulatory safety and their distinct label “MAS-Regulated Stablecoin” set them apart from other stablecoins, facilitating their promotion. Furthermore, due to their compliance, they gain greater acceptance from traditional financial institutions and encounter fewer obstacles when dealing with banks for deposits and withdrawals.

On the other hand, the cost associated with compliant stablecoins should not be overlooked. MAS has explicitly defined qualification requirements for issuers in terms of capital adequacy, solvency, and scope of operations. In contrast, existing stablecoin issuers are not subjected to such restrictions. Moreover, there is an issue of fairness in the market — MAS stipulates that banks issuing stablecoins do not require the Monetary Authority of Singapore Payments Institution (MPI) license, whereas non-bank issuers need to apply for it. The process of obtaining an MPI license typically spans around 1–2 years, and it involves rigorous checks on a company’s qualifications. Since the implementation of the Payment Services Act (PS Act) in 2019, the number of companies obtaining an MPI license remains limited. Consequently, issuing compliant stablecoins in Singapore demands substantial investments in terms of time, human resources, and finances.

In conclusion, under the current MAS stablecoin regulatory framework, there is a higher probability for banks or financially robust corporations to issue “MAS-Regulated Stablecoins,” while non-bank small and medium enterprises might find the current policy less conducive.

Follow us

Twitter: https://twitter.com/WuBlockchain

Telegram: https://t.me/wublockchainenglish