Source:

https://twitter.com/Loki_Zeng/status/1668085479970045954

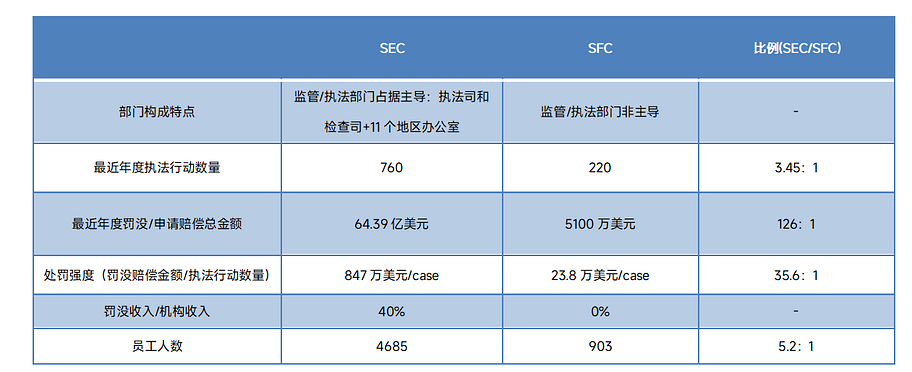

Previously, we discussed whether the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) would follow the footsteps of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in defining securities and actively regulating, investigating, and imposing fines. The key to answering this question lies not only in their stated goals but also in their actual actions. There is a simple approach to answering this question: understanding the structure and personnel composition of the SEC and SFC.

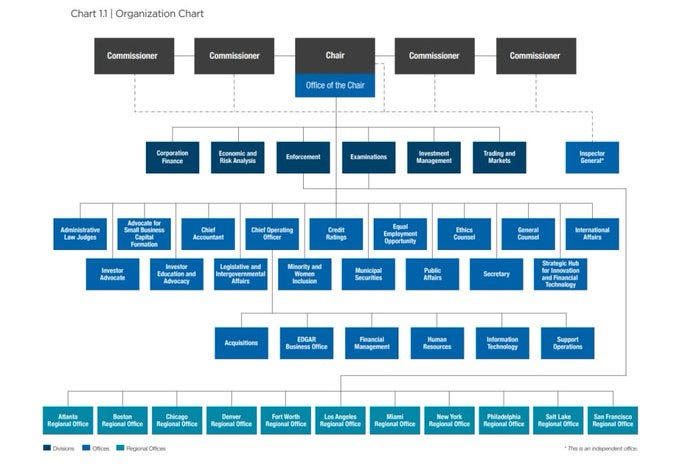

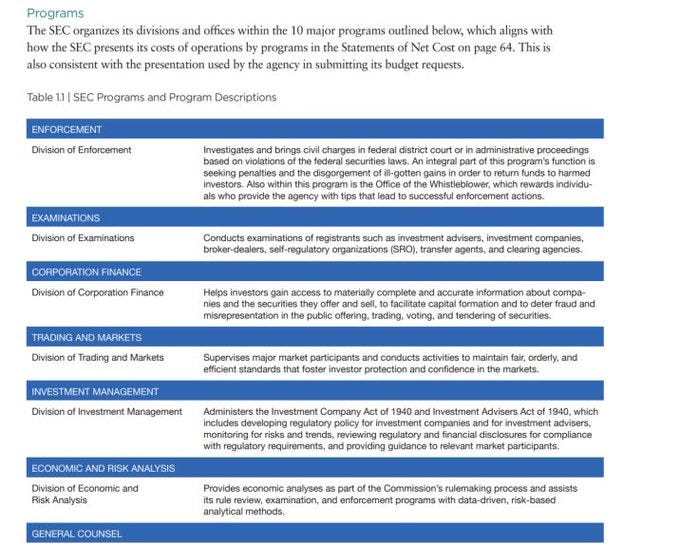

Let’s start by examining the structure of the SEC. At the top, there is a committee composed of a chairman and four commissioners. It includes six divisions, one Office of the Inspector General, and eleven offices. Additionally, there are eleven regional offices that report to both the Division of Enforcement and the Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations.

From the organizational structure, we can observe that the Division of Enforcement and the Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations appear to be the most crucial among all the divisions. In the descriptions of various departments, we can also see the prominent roles of the Division of Enforcement and the Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations.

Furthermore, there is compelling data regarding the financials of the SEC. The SEC’s funding comes from three main sources:

1. Congressional appropriations,

2. Securities transaction fees and registration fees, and

3. Disgorgements and penalties.

The disgorgements and penalties can be further divided into two parts:

- For cases requiring victim compensation, the disgorged funds are used to compensate the victims and are deposited into the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s General Fund.

- For cases not requiring victim compensation, the disgorged funds are allocated to the Investor Protection Fund, whistleblowers (providers of investigation leads), and funding for the Office of the Inspector General’s investigations.

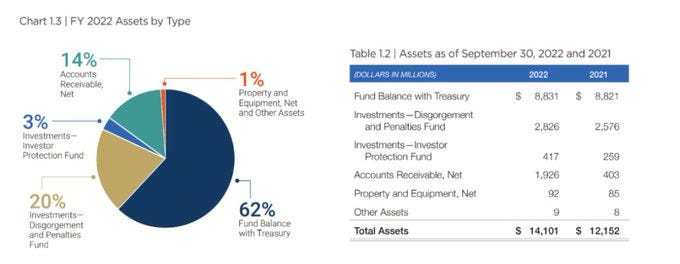

Let’s now examine the SEC’s balance sheet. According to the 2022 annual report, the SEC’s total assets increased from $12.2 billion to $14.1 billion, a growth of $1.9 billion. The investment portfolio increased by $400 million, and accounts receivable increased by $1.5 billion, with a significant portion of these figures attributed to disgorgements and penalties. The investment portfolio figures have already accounted for regulatory expenses.

In addition to disgorgements and penalties, the SEC has an allocated budget of $50 million in reserves approved by the OMB for 2022, a budget of $390 million for the Investor Protection Fund, transaction fees of approximately $1.8 billion, and registration fees totaling $640 million. It is evident that disgorgements and penalties have become a significant source of revenue for the SEC.

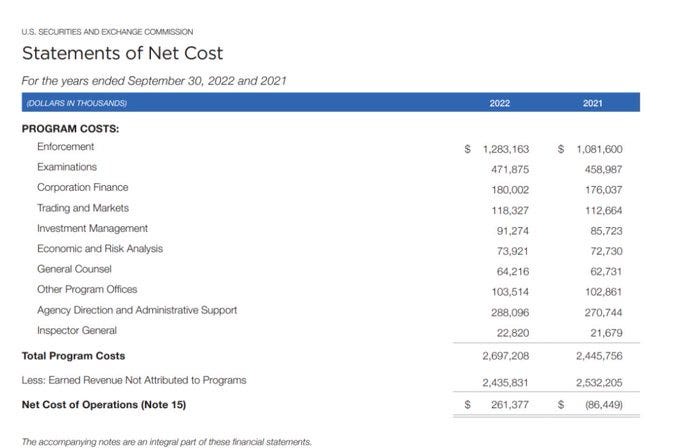

Now, let’s turn our attention to expenditures. It is notable that the Division of Enforcement and the Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations have the highest net expenditures, amounting to a combined total of $1.75 billion, accounting for 65% of the total expenditures. These expenditures translate into enforcement actions. According to another public article by the SEC, a total of 760 enforcement actions were filed during the 2022 fiscal year, a 9% increase from the previous year, including 462 new or “stand-alone” enforcement actions.

These enforcement actions resulted in substantial monetary penalties. The total amount ordered to be paid reached $6.439 billion, including civil penalties, disgorgement, and prejudgment interest, setting a historical record for the SEC, surpassing the $3.852 billion in the 2021 fiscal year. Within the total amount, civil penalties alone reached $419.4 million, also a historical high.

Under this system, the SEC has provided substantial rewards to whistleblowers, issuing approximately $229 million in awards in the 2022 fiscal year, marking the second-highest amount in history. Simultaneously, the number of whistleblower reports received by the SEC reached an all-time high of 12,300. Gensler’s request for additional resources, such as increasing the number of SEC staff from 4,685 to 5,139, is thus justified.

In summary, the SEC’s enforcement approach is not difficult to comprehend — it is a form of retrospective enforcement. The aim is to involve as many individuals as possible in the market and allow them to take action, followed by investigations, evidence collection, prosecution, and ultimately penalties. Therefore, it is not difficult to understand the SEC’s assertion that everything is a security except for Bitcoin. Expanding the scope of enforcement is the first step, but whether enforcement actions are taken and prosecutions succeed depends on many factors.

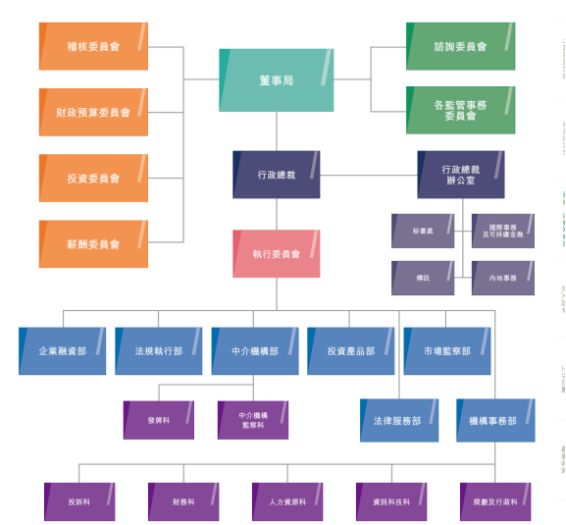

Now, let’s turn our attention back to the SFC. The structure of the SFC differs significantly from that of the SEC. Within the SFC, the departments directly involved in regulation are the Market Surveillance Division and the Intermediaries Supervision Department, which also includes the Licensing Department, closely associated with the licensing system that we are familiar with.

According to the SFC’s 2021–2022 Annual Report, a total of 220 cases were investigated throughout the year, resulting in 168 civil proceedings initiated, and a total of HKD 410.1 million in fines imposed on licensed entities and individuals. In addition to enforcement actions, another important statistic is that the SFC received 7,163 license applications and processed over 38,000 licensing-related documents through the WING system.

Regarding specific enforcement categories, although the SFC mentioned that it will take decisive enforcement actions against unlicensed platform operators “where appropriate,” the majority of enforcement cases still involve traditional financial misconduct such as insider trading and market manipulation, corporate fraud and misconduct, negligence by intermediaries, and inadequate internal controls.

In terms of revenue and expenditure, the SFC’s structure is relatively straightforward. In the 2021–2022 fiscal year, the SFC’s total revenue was HKD 2.247 billion, with transaction levies accounting for 95.3% and other income (primarily from market participants) comprising 6.7%. Confiscated income did not appear in the SFC’s revenue breakdown. Personnel expenses constituted 75.7% of the expenditures. According to the annual report, as of 2022, the SFC had a total of 913 employees.

Furthermore, based on this data, it is not accurate to claim that the SFC earns significant revenue through licensing. Market transactions contribute the majority of the SFC’s income. License fees for licensed corporations range from HKD 47,000 to 1.297 million per activity, while license fees for licensed representatives range from HKD 1,790 to 5,370 per activity. The 3,231 licensed entities and over 40,000 licensed individuals do not generate substantial revenue.

Based on past data, the SFC does not exhibit the same motivation as the SEC. Additionally, the SFC lacks the same level of enforcement capabilities as the SEC. With only 903 employees, the SFC’s staff is already occupied with the complex operations of the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Futures Exchange, processing a significant volume of license applications, maintenance and inspections, and even promoting philanthropy and making the world a better place. It is challenging for the SFC to allocate additional resources for proactive enforcement.

Based on the above data, it can be observed that the SFC does not possess the same policy inclinations as the SEC. Both the SFC and the SEC fundamentally operate under the principle of treating similar activities, risks, and regulations equally. While the SEC exhibits strong regulatory tendencies towards cryptocurrencies, it maintains the same inclinations towards other financial institutions. Therefore, the likelihood of the SFC treating cryptocurrencies differently is highly unlikely.

In conclusion, I believe that the probability of the SFC conducting large-scale enforcement actions like the SEC is very low. For entrepreneurs, as long as they do not explicitly violate current laws and regulations in Hong Kong, there is no need to worry about regulatory pressures. However, I do not argue that the “Hong Kong market” and “active licensing” are suitable for every project. After all, the application and maintenance of licenses entail considerable costs. Even without a license, there are still plenty of other Web3-related activities that can be pursued in Hong Kong. While there may not be concerns about SEC-like regulatory pressures, it is still worth considering whether a license is truly necessary for each aspiring participant.

References:

https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-206

https://www.sec.gov/files/sec-2022-agency-financial-report.pdf#chairmessage